By Dallas Cant*

The perimeter of Canadian Journeys, a gallery at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, is lined with story booths that name “steps and missteps on the road to greater rights for everyone in Canada” (wall text). In the centre of the gallery are touchscreen digital memory banks (basically, computers) where visitors can scroll through stories based on topic and time period. These banks provide a wealth of information beyond the story booths, but their subtle stature and placement against other, more sensory-stimulating installations draw visitors away from them, leaving them largely untouched. Right to Safety, the only representation and story of sex work in the Museum, is nestled into one of these digital memory banks, effectively hidden from view.

Photo credit: Dallas Cant

In the broader public imaginary, sex work tends to be constructed within simplistic dichotomies of violence/pleasure and victimization/agency, obscuring the complex forms of labour and experience it involves. Extremes of violence and victimization have been mobilized to argue that sex work itself is something inherently violent and harmful. In this way, violence enacted upon sex workers becomes an expected and justified experience. To counter this harmful understanding, activists like COYOTE have talked about sex work as a liberatory and progressive labour, one that may push against sexual politics bound to marriage and monogamy. As sex work scholar Elizabeth Bernstein has suggested, however, this kind of celebratory politics has come primarily from sex workers with white and class privilege (77). What these extremities lack then is attention to how structural inequalities inform experiences within the sex trade. Through this lack, intersections of white supremacy, colonialism, and transphobia are seen as irrelevant to understanding sex work. This neglects the lived experiences of sex workers, particularly those who are racialized, Indigenous, and genderqueer. While neither entirely violent nor entirely celebratory sentiments prove useful in capturing the realities of sex work, they comprise how sex work is publicly imagined and in turn, regulated.

In using the exhibited story Right to Safety as a starting point, I consider how the Museum’s representation of sex work contributes to the sex work imaginary. While this particular “exhibit” is small and not very visible, especially when compared to the scale of the Museum’s permanent installations, I see value in holding national representations of sex work accountable as they inform how non-sex working publics and allies are able to talk about and support sex workers.

Photo credit: Dallas Cant

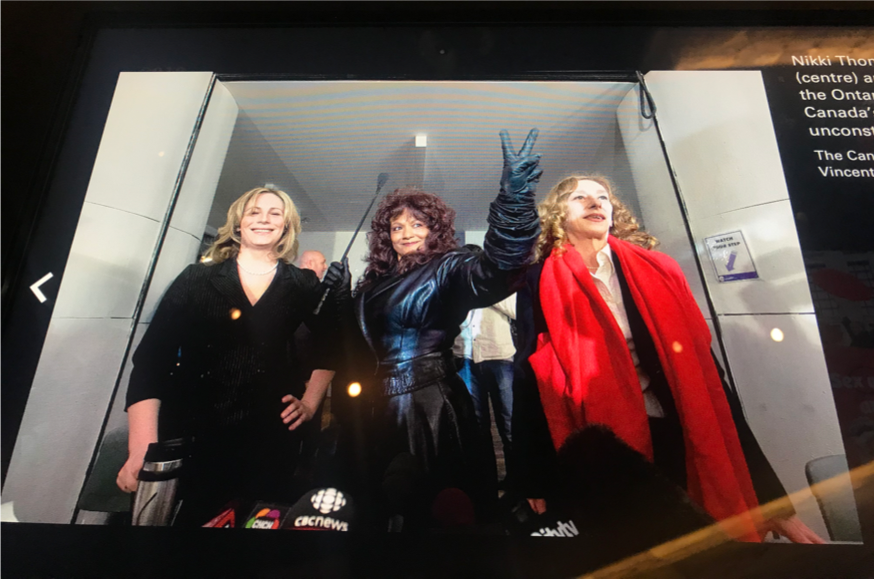

Right to Safety outlines a court case initiated by Terri-Jean Bedford, Amy Lebovitch, and Valerie Scott in 2007. This case argued that Canada’s existing laws regulating the sex trade violated the right to security of the person, protected under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms [1]. The digitized story also references the introduction of The Protection of Communities and Exploited Persons Act (Bill C-36), which was implemented seven years following the success of Bedford vs. Attorney General of Canada[2]. For context, Bill C-36 criminalizes the act of purchasing sex and negotiating the selling of sex in public. The bill also restricts the ways that sex workers are able to advertise their services online. While selling sex is legal under Bill C-36, it criminalizes crucial components of how sex workers generate income, which makes it very difficult to work legally as a sex worker in Canada (Winnipeg Working Group). Three photos accompany the textual portion of Right to Safety, one featuring Bedford holding up her leather riding crop in prideful celebration alongside Scott and lawyer Nikki Thomas.

The criticality of Right to Safety took me by surprise, naming that prior to 2007, “sex workers in Canada have worked without human rights protection” and that Bill C-36 has “further criminalized prostitution,” forcing workers “to operate alone in isolated areas” (Right to Safety). Considering the Museum’s national status, I had expected that they would side with the state’s understanding of Bill C-36 – that the bill better protects workers from the exploitation of sex work (Department of Justice Canada). Instead, the Museum positions Bill C-36 as worsening conditions for sex workers, something the state has not yet admitted to. By naming that Canadian law contributes to harmful working environments for sex workers, the Museum disrupts the common understanding that sex workers experience harm because of their profession alone. While this is a move toward a critical assessment of sex work in Canada, the conversation stops there.

Right to Safety leaves racism, settler colonialism, and white supremacy in relation to sex work entirely unaddressed. This is a significant silence, which allows the Museum to speak about sex work as if removed from the legacies that the Canadian state is built upon. As queer sex worker and theorist Zahra Stardust argues, refusing to name systemic inequalities constructs an illusion that sex workers are unaffected by privileges and marginalization (68). Right to Safety’s narrative exists within this illusion, upholding an imaginary that suggests institutionalized racism has nothing to do with sex work in Canada. To the Museum, naming the structural, social, and legal inequalities within the sex trade is seemingly too much, too disruptive, and as education scholars Alice Pitt and Deborah Britzman might pose, too “difficult.” Pitt and Britzman write about “difficult knowledge” as content that asks viewers to interrogate their own understanding of, and relationship to, the world (756). By refusing to tackle representation that asks viewers to engage in questions about race, privilege, marginalization, and sex work in Canada, the Museum opts to maintain a simplistic and imagined illusion of sex work.

Photo credit: Dallas Cant

This refusal continues, showing itself in a much more visible way than the hidden location of Right to Safety. Above the story booths in the Canadian Journeys gallery is a large digital collection of images. These images feature the faces of those represented throughout the gallery, including Bedford (second from the left, top row, in the image above). While Bedford is seen with her whip in full view in the digital banks (see Fig. #2), the same photo has been carefully cropped here for the border, rendering the whip invisible[3]. As queer theorist and museum scholar Jennifer Tyburczy writes about other instances where a whip has appeared in museum contexts, the whip in public view evokes an excited curiosity and, perhaps, an unsettling association with enslavement, discipline, and BDSM[4] communities. While white slave owners have used the whip to carry out non-consensual torture on Black subjects, the whip has too been adapted as a device to engage with consensual erotics of pain, pleasure, domination, and submission. The whip then, is not simply an object, but a symbol of two inseparable histories: the transatlantic slave trade and kink/BDSM cultures. Tyburczy argues that because of these interimplications, the whip can be used as a “tool for examining sexual values,” namely the “fears, anxieties, and affections regarding race and sex” (193). In this way, the cropping of the whip can be read as an intentional choice, one that refuses to acknowledge the importance of discussing whips and their ongoing relationships to white supremacy and kinky sex. These discussions are, however, imperative to unpacking the complexities of race, sex (work), and systemic oppression in Canada. So it seems to me that the whip and all it evokes could act precisely as a tool for the Museum to further its conversation on sex work, which, as it is, stops short of unsettling assumptions about race and systemic oppressions. If the whip remained alongside Bedford, would difficult conversations about race and sex work be supported in the Museum? In other words, could the Museum bring the whip into clearer focus (rather than cropping it out of the frame) as a method to turn towards difficult knowledge about sex work in Canada?

As a continuance of this “turning toward,” in my research with Museum Queeries, I have sought out histories of sex work in Canada that move beyond the silences of Right to Safety. I engage with these histories by beginning to understand them as bound to the land that the Museum, and I myself, occupy. Therefore, I have looked to sources that account for histories of sex work in Winnipeg, such as, the Manitoba Gay and Lesbian Archives and Amy Catherine Wilkinson’s “Sex work and the Social-Spatial Order of Boomtown.” Rather than shy away from examining how systemic inequalities and race emerge within these histories, I have turned directly to them. This has allowed me to carry out my research in a way that is attuned to difficult histories of sex work in Winnipeg. These histories matter, and they deserve space and critical attention. As Indigenous scholar Sarah Hunt writes, “remembering and naming histories of violence and inequality in the sex trade” must not simply be viewed “as injustices of the past, but rather structures of the present” (98). In other words, histories of sex work that account for intersections of systemic oppressions help to understand the contemporary socio-legal contexts that sex workers navigate today. This work complicates the simplicities of the sex work imaginary to ask critical questions about race, privilege, and marginalization within or around sex work in Canada.

[1]Protected under section s.7 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

[2]You can access the full decision of Bedford vs. Attorney General of Canada here.Pivot Legal offers a summarized version of the proceedings, available here.

[3]Due to how close Bedford is holding her whip in the digital memory bank photo, including this image without the whip would require close editing. The other images on the digital photo border appear to have wide framing, often exposing the background behind the person featured. Bedford’s picture does not include any background. Because a wider frame would expose the whip, I speculate that the close cropping of Bedford’s image was intentional.

[4]BDSM defines a community who engages in consensual acts of bondage and discipline, domination and submission, and sadomasochism.

Works cited:

Bedford v. Canada (Attorney General). Supreme Court of Canada. 2014.

Bernstein, Elizabeth. Temporarily Yours: Intimacy, Authenticity, and the Commerce of Sex. University of Chicago Press, 2007.

Bennett, Darcie. “Supreme Court Rules in Support of Sex Workers.” Pivot Legal, 20 Dec. 2013.

Canada. Department of Justice. Prostitution Criminal Law Reform: Bill C-36, the Protection and Communities and Exploited Persons Act, 2014.

Canadian Bar Association. Bill C-36, Protection of Communities and Exploited Persons Act. National Criminal Justice Section and Municipal Law Section of the Canadian Bar Association, October 2014.

Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Part 1 of the Constitution Act, 1982, being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), 1982, s. 7.

Hunt, Sarah. “Decolonizing Sex Work: Developing an Intersectional Indigenous Approach.” Selling Sex: Experience, Advocacy, and Research on Sex Work in Canada, edited by Emily van der Meulen et al., University of British Columbia Press, 2013, pp. 82- 100.

Pitt, Allison and Deborah Britzman. “Speculations on Qualities of Difficult Knowledge in Teaching and Learning: An Experiment in Psychoanalytic Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, vol. 16, no. 6, 2003, pp. 755-776.

Text, Right to Safety, Canadian Museum for Human Rights, Winnipeg. Accessed 12 May 2019

Tyburczy, Jennifer. Sex Museums: The Politics and Performance of Display. University of Chicago Press, 2016.

Wall text, Canadian Journeys, Canadian Museum for Human Rights, Winnipeg. Accessed 12 May 2019.

Wilkinson, Amy Catherine. Sex Work and the Social-Spatial Order of Boomtown: Winnipeg, 1873-1912. Master’s Thesis, 2015.

Winnipeg Working Group. “What to Expect from C-36.” Sex Work Winnipeg, 2014.

*Dallas Cant is currently working towards completing a B.A. in Women’s and Gender Studies at the University of Winnipeg. They are interested in exploring queer embodiments, curatorial methodologies, and queer cultural production in relation to sex work. Dallas recognizes the creative form as medium of resistance and incorporates digital photography, poetry, and hand stitching into their research-creation methodology. Currently, they are developing an undergraduate course in sexuality and online communities alongside Dr. Fiona J. Green (University of Winnipeg). Dallas also works as a research assistant with the Greenhouse Artlab to explore and think queerly in relation to bee eco-cultures. In the future, Dallas intends to pursue an M.A. in sexuality studies.