By Mika Castro*

The Manitoba Museum, true to its name, displays information about Manitoba’s rich history. Its galleries tell us much about Manitoba’s natural environment, from its arctic to its boreal forests and parklands. The museum also houses Manitoban/Winnipeg-based histories, such as the significance of the Hudson’s Bay Company in Manitoba and the 1920 Winnipeg Strike. For the most part, though, the museum itself appears to be a classic natural history museum. It contains stuffed and stitched animals encased in glass walls, preserved plants in manicured backgrounds, and hallways of dioramas, some of which are life-sized human bodies within their presumably natural contexts. Self-touring around the main floor, one will find easily digestible information about evolution, brief descriptions about ecosystems, and quick bites about types of Manitoba’s fauna and flora.

However, even if the museum appears to be a stereotypical conglomerate of science exhibits, it was hard not to enjoy myself as I weaved through the museum. There always seems to be something to do: objects to touch, videos to interact with, buttons to press, sounds to hear and lights to turn on, levers to press, and even, at one point, things to smell. Much of my experience within this museum involved active engagement with the galleries. The Manitoba Museum seems to me not a space for the quiet contemplation of information, but a space for play; one that invites its visitors to imagine beyond the material presented.

It is no wonder then that the museum is usually full of children on school field trips. Throughout my visits at the museum in search for research content, I found it hard not be distracted by the children around me and the snippets of conversations that they had with each other. I recall coming across this one child pointing to what appeared to be a fat brown worm and having a dynamic conversation with another child about some experience they had with a slug one time.

Initially, I went into the museum to look at Manitoba’s stories of immigration, but, in following the lead of the children, I began to see the museum as a space for fantasy, one that is open to queer critical thinking. I wondered how this fantastical space might allow me to “read in” my own research interests, mainly that of queer immigrant stories. Seeing as how some of these conversations involved personal experience, I also wondered how I could use my own experiences, especially as a Filipino person, to guide my research. Could I, somehow, read in my own stories and those of others from the Filipino community to illuminate queer/immigrant/Filipino narratives that might not even be in the museum in the first place? Being able to read in these stories rather than just being in search for them might open up a different way for me to conduct my research in the museum.

Learning from the Dwende

As I walked through the hallways of the boreal forest gallery, I thought of how much some of the galleries reminded me of home. I thought of the plants and how, even though much of them were unfamiliar or weren’t present back in the Philippines, they made me think of the stories that my parents, aunts, and my grandmothers used to tell me growing up. One particular memory that came to mind was one hot day before the third grade. At the time, my brothers, my mother, and I were walking in our tsinelas¹ by the old church near our grandmother’s house. I remember the church being mostly worn-down, its sides and surrounding pavement cracked under the hot Philippine sun. My brothers and I loved to walk by here because it was the fastest way to access what I now know to be a blocked-off yard, but was then a ground of infinite space. All the way from the church to the yard, wild grass took over the earth, even in the small spaces between the broken pavement where sunlight could still peek its head through. Dotted across the sides of the concrete and the grass were small mounds of dirt bursting with neat lines of marching ants.

Before my brothers and I could start sprinting across the grass, Mama warned us to watch where we stepped so as to not step on the anthills. She warned us of the creatures called the dwende who may be living deep underneath these hills. The dwendes, she explained, are nature spirits that usually live in anthills, trees, caves, or around spots in nature that simply feel mystical. They are usually thought of as tiny and old creatures, but are mostly invisible. Here and there, in places like the bukid² or the gubat³, they were busy guarding nature and creating mischief or concocting luck whenever it pleased them. From then on, I thought of the dwende every time I was in the presence of nature even though I have not seen this creature once. It was clear that I didn’t need to see them to know that they were real. Somehow, imagining these creatures running around the museum space and hiding themselves in the exhibits made me think that they had lessons to teach me about the museum. In thinking about their invisible presence, I began to ask myself what it meant to be visible or invisible in the museum space and what this might mean for the Filipinx/o immigrant stories and histories that may or may not be present in the museum. More importantly, I wondered about what this (in)visibility might mean for Filipinx/o immigrants whose stories and histories may or may not be present in the museum.

The (In)visible Immigrant in the Museum

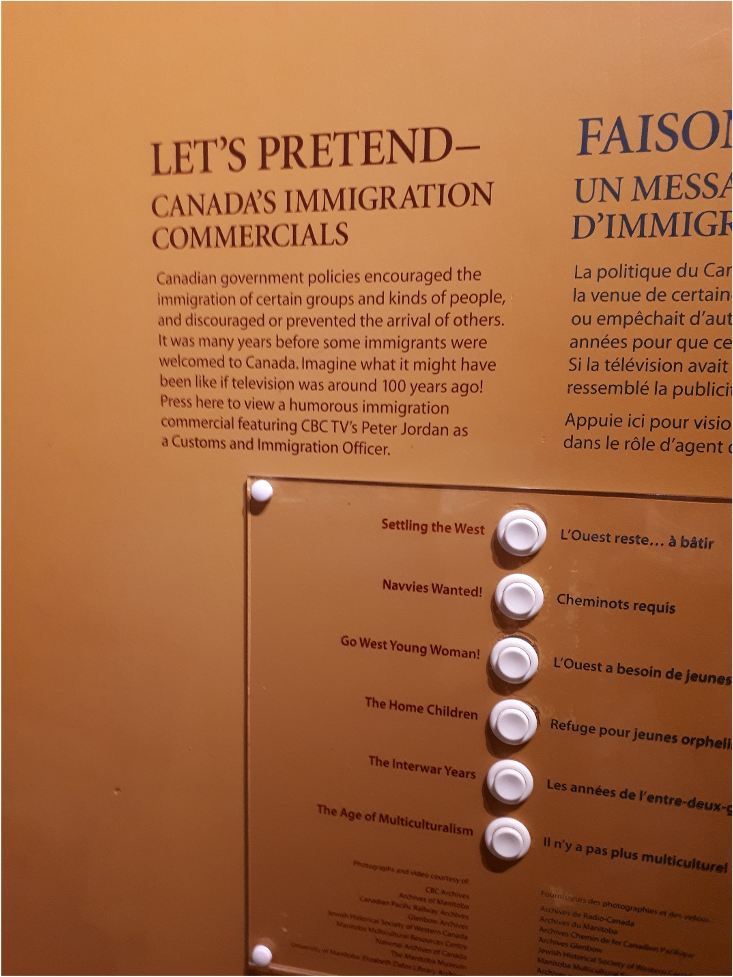

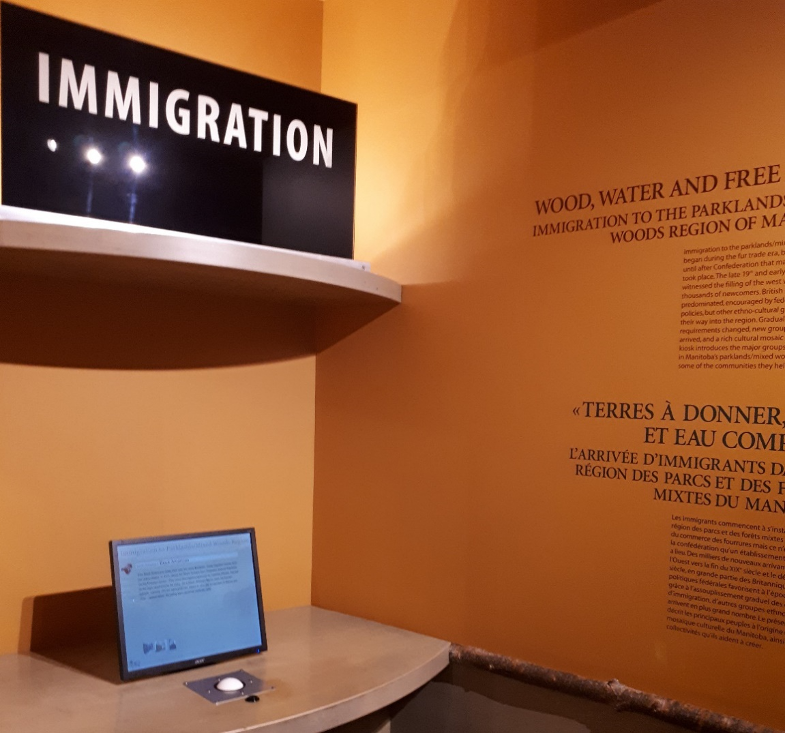

Galleries on immigration begin to appear nearing the end of the Parklands/Mixed Woods area of the museum. These galleries include “The Commerce of Migration”, the “Wood, Water, and Free Land” Gallery, and the newly added “Winnipeg Gallery”. They discuss the history of immigration of a diverse number of groups to Manitoba’s Parklands area. The first gallery “The Commerce of Migration” contains videos that foreshadow how the museum will portray immigration in the later galleries. At the press of a button, the gallery presents skits of immigration commercials. Each video is on a different era of Canadian migration, from the settlement of European families in Western Canada to present Canada as a popular site for global migration. Going through the videos, it was startling to see how they portray Canada’s timeline of non-diversity to sudden diversity by ending with a skit titled “The Age of Multiculturalism.” This progress narrative seems to portray Canada as a nation that has gone through an extensive and surprising character development where suddenly, without explanation, it opened its arms and softened its heart to immigrants all over the world.

The panel next to this gallery called “Cultural Diversity” substantiates this portrayal by saying that “[a]lthough different cultures [within Canada] sometimes clashed with one another, the value of cultural diversity gradually was recognized. Today the rich cultural mosaic of the region is celebrated.” This theme of a diverse Canada is one that is prevalent throughout these galleries about immigration. Doing so seems to address the influx of non-European immigrants in Canada in the 20th century, which is to highlight the presence of racialized immigrants.

It wasn’t until I reached the “Immigration” kiosk under the “Wood, Water and Free Land” exhibit did I see information about the immigration of certain ethnic groups to Manitoba. Unlike the other displays, the kiosk briefly points out the Canadian government’s restrictions on the immigration of people from “non-traditional points of origin” (which is to say racialized people) and their gradual acceptance in Manitoba. However, this is all done without explaining the reasons for the restrictions or the later approvals of these groups.

Among these groups were the Filipinos who mostly began to arrive in Manitoba in the mid-20th century. According to Historian Jon G. Malek (2019), Filipino migrants first came to fill the demand for garment workers and healthcare professionals during the 1960s-1980s (49). At the time, Winnipeg in particular faced a high demand for garment workers, mostly due to its waning European (mostly Italian) workers who began to break away from the garment industry because of poor working conditions and wages (106).

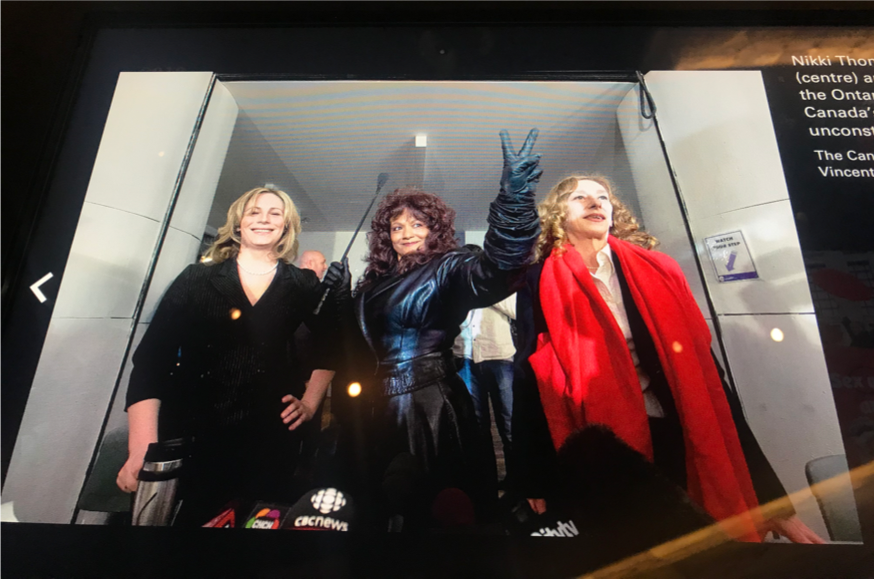

One particular figurehead who can attest to early Filipino immigration is Perla Javate, the current president of the Philippine Heritage Council of Manitoba and community liaison officer for the Winnipeg School division. In an interview with CBC, Javate tells the story of how she first came to Canada as a social worker to bring in Filipinas for Manitoba’s growing need for garment workers in the 70s. She recounts her feelings of frustration when she first came to Winnipeg with the other women and their experiences of having to navigate “cultural difference[s].” These differences might be interpreted as difficulties of having to assimilate to a predominantly white Winnipeg because she notes how, at the time of her arrival, Winnipeg wasn’t as “multicultural as it is today” (“CBC Asks: How is the Filipino experience in Manitoba changing?”). Although her history with the garment industry and how she came to Winnipeg is not covered in the Manitoba Museum, her image is shown in the new Winnipeg Gallery. She is part of the gallery’s “Personalities Wall” which presents thirty Winnipeggers who have had an impact on the city’s communities and present history. Within this wall she holds the title of “Multiculturalism promoter” and is described as someone who “focuses on promoting Filipino culture and multiculturalism.”

The Manitoba Museum surrounds multiculturalism in tones of celebration. It is seen as a great feat for Canada to include so many groups of different races and ethnicities, making Canada appear as this accepting country that is welcoming of everyone, regardless of background. This renders immigration, especially the migration of racialized peoples, as a positive process as it only adds to the country’s diversity. The museum also seems to suggest that although Canada contains people of different racial, ethnic, and cultural backgrounds, these populations are able to live harmoniously with one another. This use of multiculturalism is one that can be called “liberal multiculturalism.” Critics of liberal multiculturalism, such as Stephen May and Christine E. Sleeter, say that although it calls for the recognition of different ethnic/cultural groups, it “abdicates any corresponding recognition of unequal, and often untidy, power relations that underpin inequality and limit cultural interaction” (4). Similarly, the framing of multiculturalism within the museum can also be interpreted as fostering “multicultural nationalism”, which is described by Caitlin Gordon-Walker as a way of establishing nationalism through the recognition of minorities within a nation (specifically Canada) and is subsequently conflated with the nation’s apparent “inclusivity” and “benevolence” (5). This positive image works to mask the ways that Canada participates in “practices of exclusion and violence within, at, and beyond [its] borders” (9). It is as if, almost paradoxically, the museum’s goal of showcasing its racialized migrants only actually obscures the systems and histories of racism that affect them within Canada.

Although the museum’s Immigration kiosk hints at the problems that recent immigrants face in Canada, such as “discrimination and issues related to human rights and labour practices,” it does so in a way that distances Canada’s role in the presence of racism throughout and after the immigration process. It is as if these experiences simply just occur or that they aren’t tied to the nation in any way. Indeed, racism has always been present in Canada’s early immigration policies such as in the case of The Immigration Act of 1952, wherein Canada held the power to deny migration based on nationality, ethnicity, “unsuitability” to adapt to Canada’s environmental climate, and perceived “inability to become readily assimilated” (“Immigration Act, 1952”). For Filipinos (among other groups, such as and especially Black people), one of the ways in which their prohibition was justified by the Canadian government was because it was believed that they wouldn’t be able to adjust to Canada’s climate (Knowles 169; Malek 83-86). Climate-based policies such as the one included in the Immigration Act have been present in previous Canadian immigration policies and have consequently privileged the entrance of white immigrants over racialized immigrants. These policies have often been used to hide the reality that Canada simply did not want to accept immigrants of colour into the country (Knowles 91, 170). Later on, however, shifts in immigration policies (such as the beginning of the Points System⁴, for example), and pressure from the Philippine government led to Canada finally allowing Filipinos within the province to fill up needed or unwanted labour sectors (Malek 49).

Even now, however, Filipinos still face problems after years of being able to enter Manitoba. From the same CBC interview, Perla recounts the difficulties that Filipinos face, saying that “the challenges when [they] first came are still here” especially when it comes to job security. In this interview she says:

“[Filipinos] usually start from the very bottom… some survive and manage [sic] to land in good jobs, others [have to] divert to other professions or even lowly jobs just to be able to support their families. That I feel is a hurdle that Canada has to work on. Although there has been some changes in terms of supports from [the] government, it still is not enough (‘CBC Asks: How is the Filipino experience in Manitoba changing?’). “

Perla Javate’s interview points out Canada’s involvement in the marginalization of Filipino immigrants in a way that the Manitoba Museum could not, even when the museum itself displayed Javate as Winnipeg’s own “multicultural promoter”. This limits the museum’s celebration of multiculturalism as a celebration at the superficial level, where it applauds the presence of people of colour rather than examining its relationships with them. This begs the question of whether multiculturalism should be celebrated in the museum if its celebration only sanitizes Canada’s relationship with its racialized immigrants.

Marisa Largo, a Filipinx artist and educator, adds to this point when she talks about how the representation of minorities is often relegated to progressive optics or used as evidence for Canada’s exceptionalism. She says that

“When minoritized subjects are made visible within official multicultural discourse in Canada, such visibility often continues to legitimize the interests of the nation-state, and reproduce colonial and neoliberal narratives. To be visible is simply not enough… Simply being visible in various sectors of society such as arts and culture does not guarantee social justice and inclusion” (99).

Even when racialized immigrants are included in the museum, their presence does not interrogate how they have shaped Manitoba’s or Winnipeg’s histories in the first place. Instead, they are tokenized in the interest of upholding Canada as a benevolent country. In this way, their visibility in the museum only serves to make their real histories invisible.

It is important to note that there are layers to visibility and invisibility when it comes to the representation of Filipinos in Manitoba. Whereas truthful accounts of Filipino migrant experiences are only partially visible when it comes to Canadian or Manitoban discourse, queer Filipinx stories, on the other hand, are invisible. Queer, Manitoban Filipinxs are often left out of discussions of Filipino immigration or are not seen as fitting with the image of what a Filipino Manitoban should be. A uniquely Manitoban perspective of queer Filipinx experience is not only underrepresented in academic literature, it also hardly appears in Manitoban or Manitoba-based Filipino media outlets.

However, there is a recent exception to this invisibility when it comes to the work of Ally Gonzalo, a queer, more specifically bakla⁵, artist whose work has been featured in CBC and has even appeared in an exhibit within Aceartinc, an art centre in Winnipeg. Gonzalo’s exhibit, “Bakla”, shows a series of black and white portraits of bakla people who are part of the Filipinx diaspora in Winnipeg. In these portraits, Gonzalo gives each subject the space to tell their own story, be it through the photograph or the descriptions that come with each one. The exhibit makes a statement that Winnipeg has its own “thriving bakla and Filipinx community” and that they are “an important part of Winnipeg culture” (Gonzalo).

Keeping Absent Subjects in Sight

When I am reflecting on that moment with Mama all those years ago when my brothers and I came across those anthills, I wondered why she felt it more important to warn us of the unseen rather than the swarms of ants that could have easily nipped at our feet. After teaching us about the dwende she instructed us to say “tabi tabi po”⁶, which was a way for us to pardon ourselves in their presence. She explained that saying so signals regard for the dwende’s existence and served as an indication of respect towards these creatures. It was also a way for us to let them know that we didn’t wish to harm them, which was less about a broken anthill or two but about what might happen because we couldn’t see their invisible lives. The act of imagining the existence of the dwende around the church’s path, then, was an exercise to pay attention to what was once thought to be absent from a space. Now, “reading” them in the museum serves as a model for me to reveal the memories and histories of unrepresented subjects, specifically that of Filipinx/o immigrants in Manitoba.

These Filipinx/o stories, which are stories that are otherwise invisible or excluded within the museum, must be known. In thinking of the dwende as a creature that is invisible, Filipinx/o people in the Manitoba Museum in some way occupy different statuses of partial visibility and invisibility, where their stories are either incomplete or nonexistent. What I learned from the dwende is that invisibility itself is a mode of inquiry, where acknowledging what is invisible in the first place might uncover more information about a space. This is why the histories of immigration that appeared to be missing in the museum provided a more comprehensive outlook on Canada than the histories they had on display. Most importantly, it allowed me to recognize the voices that are invisible within those already invisible groups, such as queer immigrant voices. The invisibility of their stories within the museum makes it ever more important to think about how they might influence the museum itself, whether it might be through the process of imagining childhood creatures like the dwende running free in the museum, or through other means. Imagining what is not already included within the museum space or content opens up new ways to think about what, and for who, the museum can be.

Notes:

- Tsinelas – slippers in Tagalog

- Bukid – field or farm in Tagalog

- Gubat – forest in Tagalog

- Points System – The Points System was a new system of immigration that was constructed during the 60s and followed the Immigration Act of 1952. Unlike the Immigration Act which focused on accepting immigrants based on identity (race, ethnicity, etc.), this system ranked potential immigrants based on a points basis. Points were rewarded to potential immigrants based on factors such as language ability (English and or French), education, and work experience, among other factors. Those who scored higher or were able to score above certain point thresholds (fifty points was usually the passing) were more likely to be accepted into Canada (Knowles 195-196).

- Bakla – As written by Gonzalo in his CBC article, someone who is bakla is “a Filipino person assigned male at birth but may have adopted mannerisms traditionally regarded as feminine. The term includes individuals who identify as trans, non-binary, bisexual, etc. While most bakla are attracted to men, collectively referring to them as ‘gay’ would be inaccurate as some self-identify as women” (Gonzalo).

- “tabi tabi po” – literally translates to “excuse me” in Tagalog.

Works Cited:

“CBC Asks: How Is the Filipino Experience in Manitoba Changing?” CBC News, 12 Mar. 2020.

Gonzalo, Ally. “There’s no shame in being who you are’: Photographer explores Filipino ‘bakla’ culture.” CBC News, 2 Oct. 2019.

Gordon-Walker, Caitlin. Exhibiting Nation: Multicultural Nationalism (and Its Limits) in Canada’s Museums. UBC Press, 2016.

“Immigration Act, 1952.” Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21.

Knowles, Valerie. Strangers at Our Gates: Canadian Immigration and Immigration Policy, 1540-2007. Rev. ed., Toronto, Dundurn Press, 2007, pp. 91, 169-170, 195-196.

Largo, Marrisa. “Reimagining Filipina Visibility though ‘Black Mirror’: The Queer Decolonial Diasporic Aesthetic of Marigold Santos.” Diasporic Intimacies: Queer Filipinos and Canadian Imaginaries, edited by Diaz, Robert et. al, 2018, pp. 99-118.

Malek, Jon G. The Pearl of the Prairies: The History of the Winnipeg Filipino Community. PhD dissertation, University of Western Ontario. 2019. Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 6193.

May, Stephen, and Christine E, Sleeter. Introduction. Critical Multiculturalism: Theory and Praxis, edited by Stephen May and Christine E. Sleeter, Taylor & Francis, 2010, pp. 1-16.

*Mika Castro is an undergraduate student at the University of Winnipeg who is currently majoring in sociology. She is interested in learning about the stories and lives of queer POC immigrants in Canada, most specifically how they navigate their queer identities between their Canadian and immigrant communities. She currently works as a Research Assistant with Museum Queeries.