By Mika Castro*

I immigrated to Canada ten years ago from the Philippines. Being a Filipino immigrant who happens to be queer, I look for places that tell stories about racialized queer migrant lives. These stories are important because they can be sources of familiarity in a country that can make racialized queers feel like they don’t belong. They can also offer alternatives to representations of queer lives as predominantly white, and ideally provide insight into experiences of and motivations for human migration.

The Canadian Museum for Human Rights (CMHR) seemed to be the perfect place to begin. At first glance, the Museum is promising. A quick scan through its website and social media pages makes apparent its desire to open up new discussions about human rights issues and to tell stories of diverse lives. As a Research Assistant for Museum Queeries (MQ), a project based out of the University of Winnipeg, I have been able to specifically investigate queer (hi)stories within the context of the CMHR and other museums. In this blog post, I investigate how the CMHR tells stories about queerness, ethnicity, and migration. As I see it, the museum has the potential to be more than a place of education about migration issues; it could also be a place that can facilitate feelings of connection among visitors who might also happen to be racialized, queer, or (im)migrants, or all of the above.

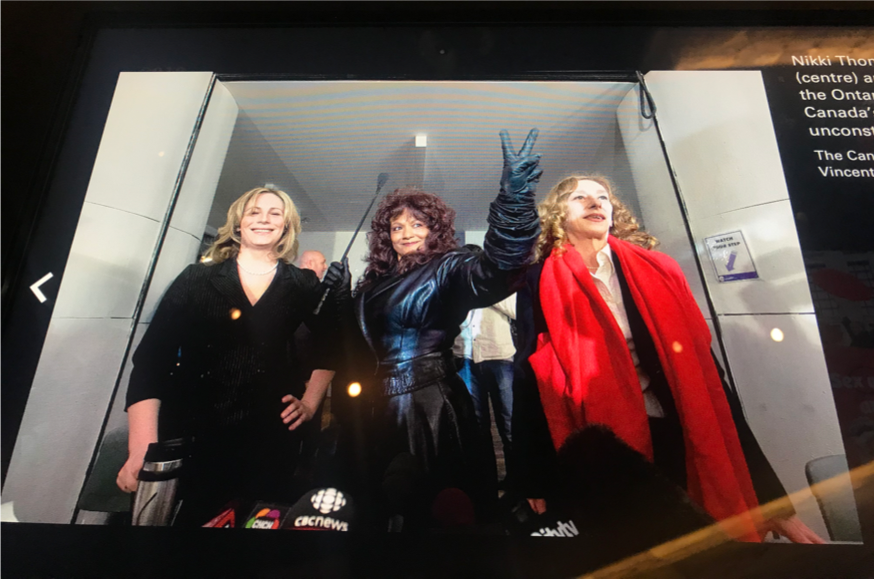

Finding the content that I initially sought in the museum, however, proved to be a challenge. For one thing, the museum’s queer content was quite hard to find. The CMHR does host an annual Pride Tour that guides its visitors through its LGBT content, but at the time of my visit the tour was not available. Finding content on queerness AND migration was even more of a challenge. I relied on CMHR staff as well as my Museum Queeries colleagues and their past research, including the blogs and audio guides they had written. Following their direction, I finally came upon the story of Arsham Parsi hidden amongst exhibits that were not obviously about “queer issues.” Parsi’s story comes up twice in the museum—first on the second floor as part of the Canadian Journey’s exhibit “Who Gets In?: Refugee Experiences at Canada’s Gates,” and then on the fourth floor in the Turning Points for Humanity exhibit under “Gender and Sexual Diversity Rights: Protecting Diversity.”

I found this double-feature in and of itself to be quite odd. One of my MQ colleagues prompted me to wonder, was the museum not able to find any other stories of queer migration to highlight? Why repeat the same person’s story twice? In any case, the two exhibits trace the journey of Parsi, a queer Iranian refugee, from his life in Iran, Turkey, and eventually Canada. These exhibits are both presented in the form of short videos that contain clips of interviews with Parsi and a compilation of pictures taken throughout Iran, Turkey, and Canada. The videos follow the same narrative of what anthropologist David Murray describes as “migration to liberation nation” (453). This common trope frames the queer refugee as escaping the oppressive homophobia of their original country only to come to a country that not only accepts but apparently celebrates their queerness without exception. In this way, sexual diversity becomes “a feature of a ‘civilized’ society, opposed to ‘uncivilized’ societies characterized by their rampant homophobia” (Murray 453). This narrative is reconstructed in the way in which the museum tells Parsi’s move from Iran and Turkey to Toronto. Parsi’s queer life in Iran and Turkey is depicted through a series of graphic images that show beatings, harsh protests, and military involvement. This reads as if queerness within these countries only ever exists in the presence of violence. In contrast to this, Parsi’s life in Canada is depicted as a queer utopia of gay pride and peaceful protests, rendering homophobia obsolete.

The CMHR presents Parsi’s journey as a refugee in a way that conflates his being in Canada with his belonging in Canada. It does so by showing Parsi as immediately and effortlessly adjusting to Canadian life after moving to Toronto, as if just being in Canada automatically translates to belonging in it. Although Parsi is not an immigrant but a refugee, and although I am not a refugee but an immigrant, witnessing Parsi’s story told in this way was a great discomfort to me. Even if I cannot understand the full extent of his experience, I cannot help but feel that the museum’s version of Parsi’s move is a sanitized one, one that is oversimplified and leaves too much out. What the museum does not discuss in Parsi’s refugee story is the precarity that comes with moving to a new country, as well as the ways in which the intersection of queerness and ethnicity affects such a move.

I cannot help but feel that the museum’s version of Parsi’s move is a sanitized one, one that is oversimplified and leaves too much out. What the museum does not discuss in Parsi’s refugee story is the precarity that comes with moving to a new country, as well as the ways in which the intersection of queerness and ethnicity affects such a move.

The process of transitioning to Canadian life after immigration can be described as one of “liminality.” This term was first described by Dutch-German French anthropologist Arnold Van Gennep as the moment of transition between two periods, when one has left or “separated” from the previous stage but has not yet been fully “incorporated” into the next (11). Later on, British anthropologist Victor Turner describes liminality as “an area of ambiguity, a sort of social limbo” (57). Gennep’s and Turner’s definitions have also been extended directly to the experiences of immigrants. In his article, “The Uses and Meanings of Liminality,” global studies scholar Bjørn Thomassen refers to “ethnic minorities, social minorities, transgender immigrant groups betwixt and between old and new culture” (17) as examples of peoples who experience liminality. Thomassen writes that immigrants and refugees are “betwixt and between home and host, part of society, but never fully integrated” (19). Here he highlights the in-between-ness that immigrants and refugees face when they negotiate between the ideals, culture, and overall social life between the old country and the new but never actually feeling fully “integrated” into the new. Indeed, as researchers Donnan et al. note in their study, this state of liminality leaves immigrants and refugees “caught between the moments of departure and arrival” and thus “feel[ing] as if they have never arrived” (12-13). In other words, migration is not only a process that takes place in the moment of moving between two countries, but one that continues well after landing in the new country.

Liminality can create a particular experience for queer refugees in Canada. Precisely because they may also face a crisscross of racist, homophobic, linguistic, and other barriers that make it harder to find resources to survive, particularly when it comes to employment and housing (Lee and Brotman 257). Parsi himself describes these barriers in detail in a CBC article titled “LGBTQ Refugees Face Risk and Isolation Even After They Arrive in Canada” (2019). I found this article while doing further research on Parsi’s work after I left the museum, and was surprised to find it to be opposite to the positive version of migrant experience that the CMHR documents. This article describes the “limited access to employment, housing, and particularly mental health services” that queer Iranian refugees like him face after coming to Canada. These limitations are part of why Parsi eventually founded his own organization, the International Railroad for Queer Refugees (formerly known as Iranian Railroad for Queer Refugees), which helps queer refugees “find housing, jobs, legal aid, counselling, and financial support” within Canada (see “Protecting Diversity” video). The CMHR, however, does not mention Canada’s role in these difficulties, or why they arise for queer refugees in Canada in the first place. It does not signal to Canada’s inadequacy when it comes to helping the lives of refugees, making these barriers appear as individual problems that some refugees face rather than systemic issues.

An important part of feeling like a part of a place is also finding belonging within its communities, but this can be a complicated process for queer and racialized refugees. As Lee and Brotman observe in their studies of queer refugees in Canada, “sexual minority refugees [can encounter] both racism within mainstream queer communities and homophobia/transphobia within their particular racialized community, resulting in complex intersectional experiences of exclusion” (259). Finding community is integral for queer refugees to survive within the new country after being displaced and disconnected from their support networks back in their original country. But, as Lee and Brotman find, queer refugees are sometimes put in a position where they are only seen as queer and not racialized in certain communities, or racialized but not queer in others (269). Canada’s larger problems of racism and homophobia have worked their way into communities to the point where queerness and race are seen as separate rather than intersecting.

Parsi echoes this observation in the same CBC article where he describes both his struggles as a gay Iranian man and the struggles that his queer clients face when trying to find belonging within Canada. Speaking from his own experience, Parsi finds that his skin colour and ethnicity made it difficult for him to find acceptance in Canada. He states:

I also found myself in a strange paradox. I wasn’t accepted for who I really was in Canada either. I am not white. I am not black. Eventually, I came to find out that I am not even properly “brown.” When people talked about “brown people” in Canada, I noticed they were mostly referring to people from South Asia or Latin America. But I’m from the Middle East—the middle of everything and still living in the margins (see “Village of the Missing”).

Moreover, even when he and other queer refugees do find belonging in their own ethnic community, Parsi says becoming visibly queer can be difficult because they might risk “los[ing] the emotional support of [their families] if they were to find out about [their] sexual orientation.”

I have encountered this “tip-toeing” around my queerness or my Filipino-ness in order to fit into certain communities. Being in these communities, where only a fraction of my identities seem to properly “belong,” always left me feeling fragmented. I felt the same way seeing Parsi’s story in the CMHR. It is a feeling that stems from spaces that make it seem that my experiences as a migrant, queer, and racialized person can be separated into compartments when they are really a big, messy blob of interlocking identities.

When the CMHR presents us with Parsi, a person who also embodies these intersections, their representation falls short of recognizing the messy and complicated relationships that queer migrants—whether immigrants or refugees—often have in Canada. Not addressing the particular experiences that queer migrants may have in Canada strips Parsi’s story from its nuance and makes it seem as if he did not have authority over his own story in the museum. This is especially apparent when we examine the different versions of migrant experience that the museum portrays compared to Parsi’s own CBC article. What remains of Parsi’s story in the CMHR, then, appears to be a tokenistic moment, a tale to show off Canada’s “progressiveness,” a shiny tool for displaying the museum’s seeming “wokeness.” The museum needs to engage in queer migrant stories that do not just highlight happiness, but an array of experiences that can sometimes be ugly, sad, hard to tell, and yet potentially relatable and inspiring. Our stories are complex, and these complexities belong in the museum.

Works Cited

Donnan, Hastings, et al., editors. Migrating Borders and Moving Times: Temporality and the Crossing of Borders in Europe. Manchester University Press, 2017. JSTOR.

Gennep, Arnold van. The Rites of Passage. University of Chicago Press, 1960.

Lee, Edward Ou Jin, and Shari Brotman. “Identity, Refugeeness, Belonging: Experiences of Sexual Minority Refugees in Canada.” Canadian Review of Sociology, vol. 48, no. 3, 2011, pp. 241-274. Wiley Online Library.

Murray, David A.B. “The (Not So) Straight Story: Queering Migration Narratives of Sexual Orientation and Gendered Identity Refugee Claimants.” Sexualities, vol. 17, no. 4, 2014, 451-457. SAGE Journals.

Thomassen, Bjørn. “The Uses and Meanings of Liminality.” International Political Anthropology, vol. 2, no.3, 2009, 6-27.

Turner, Victor. “Liminal to Liminoid, in Play, Flow, and Ritual: An Essay in Comparative Symbology.” Rice Institute Pamphlet – Rice University Studies, vol. 60, no. 3, 1974, pp. 53-92. Rice University.

Parsi, Arsham. “Village of the Missing: LGBTQ Refugees Face Risk and Isolation Even After They Arrive in Canada.” CBC, 22 March 2019.

*Mika Castro is an undergraduate student at the University of Winnipeg who is currently majoring in sociology. She is interested in learning about the stories and lives of queer POC immigrants in Canada, most specifically how they navigate their queer identities between their Canadian and immigrant communities.