By Chris Eastman*

From February 6-9, a gathering called the Beading Symposium: Ziigimineshin was held in Winnipeg, Manitoba. As an attendee, my intention was to be present as a beading enthusiast and occasional artist.1 Once the featured topics of the symposium were released, however, I realized the potential for a much deeper reflection on the transmission of knowledge regarding traditional and contemporary beading practices and the role museums might play in this. In addition to being a beading enthusiast and occasional artist, I am a university student and work as a Research Assistant on a project called Museum Queeries that raises critical questions about the relevance and potentiality of museums as contexts for learning and representation.

Franchesca Hebert-Spence, an Anishinaabe MFA student, artist and symposium organizer, opened the event by sharing a story about working on an academic paper for her Master’s program. In it she had written “beading is love,” and was challenged by a professor who requested citation. To this, she replied, “but from where?” How does one cite oral knowledge passed on by relatives and ancestors who do not hold academic degrees or publications?

Hebert-Spence’s anecdote reminded me of Patricia Monture’s essay “Race, Gender, and the University: Strategies for Survival” (2010), which discusses how Canadian universities, as inherently white colonial institutions, create barriers to success for women and BIPOC (Black Indigenous and People of Colour) individuals. Monture describes witnessing the denial of tenure to another scholar who published in new international journals judged to be substandard, which she believes to be code for non-Western. Scholars face trouble citing work by Indigenous knowledge keepers if only Westernized peer-reviewed journals are deemed to be reputable.2

Jennine Krauchi, a Métis bead artist and designer, also gave a talk early in the symposium on “Connecting with Our Ancestors.” Krauchi spoke specifically about a project she was commissioned to do for the Canadian Museum for Human Rights (CMHR) to represent the Métis people of Manitoba. She, along with some assistants, beaded a large 26-foot octopus bag that is now on display. A pivotal point made by Krauchi was the amount of time she had spent within the walls of another Winnipeg-based museum—the Manitoba Museum—throughout her career, leading her to view the museum as her university. This demonstrates the duality of colonial institutions like museums and universities—that they can be sites of systemic oppression and sites of reclamation at once. Krauchi’s experience demonstrates the importance of having access to museum collections and not keeping them completely locked away. Opening archival doors for individuals to view and study collections not offered on display can provide opportunities to share local and familial histories, bridging existing gaps between communities and institutions.

Towards the end of the first day of the symposium, all participants who opted in for the site visits were divided into three groups and shuttled to the Winnipeg Art Gallery, the Manitoba Craft Museum, and the University of Winnipeg to view beaded collections housed in each space.

The first stop for my group was at the Winnipeg Art Gallery (figure 1), which focused on a dedicated table with some beaded pieces from their collection on display for us to look at. We were also welcomed to wander around the other galleries and exhibitions with any remaining time we had.

Our second stop was the Manitoba Craft Museum where we had the chance to peruse lots of different beading works from their collections, and see the “behind the scenes” storage area (figure 2). A museum docent observed that there is no benefit in keeping the pieces hidden away, and so they welcome anyone from the public who wants to view the collection to contact them and make arrangements to do so. This echoes what Krauchi had discussed regarding access to archival objects and discovering alternative routes to knowledge of the past.

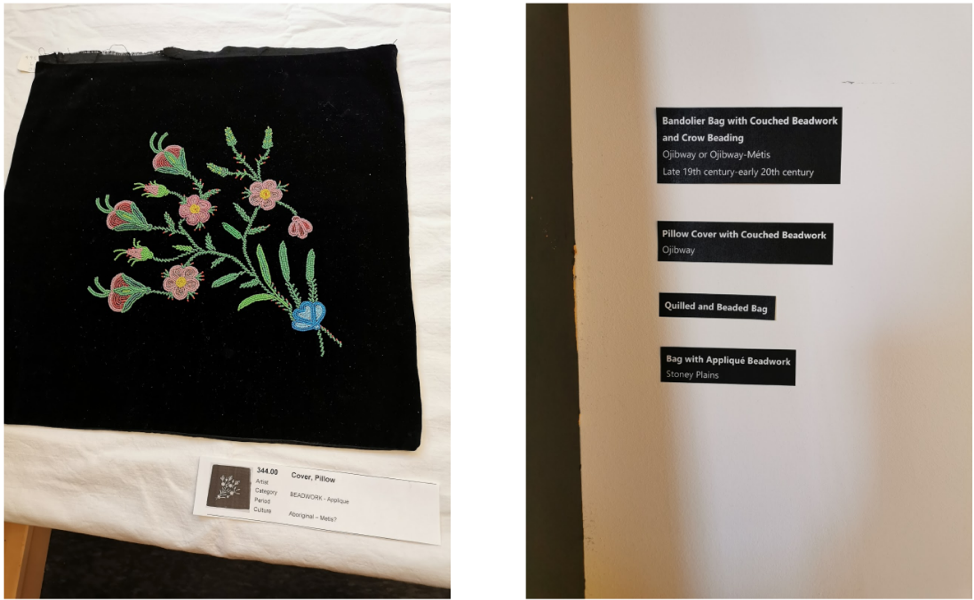

One critical thing I noticed while wandering around the Manitoba Craft Museum was that identifying tags were limited or vague on many of the pieces (see figures 3 & 4). This reminds me of Nicole Robert’s article “Getting Intersectional in Museums” (2014) in which she explains that the choices made about what information to include within exhibit labels is a reflection of what is deemed valuable by the collector.

I inquired about these labels with a museum employee who told me that they attempt to find as much information on the pieces as possible, but many works were acquired in the 1930 to 1940’s when procedures were not as they are today. While not explicitly said, this led me to wonder if many of the backstories regarding the pieces were perhaps not held with high regard in the first place and, therefore, not recorded by the original collectors. If the stories themselves had been recognized as important by collectors, might there have been more specific information such as the artist’s name, place of origin, or more concrete time frames? This lack of historical record and specificity remained on my mind throughout the day, especially since there were pieces marked as being from the 1960’s and 1970’s that lacked information too, contradicting what I was told.

In addition to the general collections in the museum, the exhibit May The Land Remember You As You Walk Upon Its Surface was also on display. This exhibit included works by Katherine Boyer, Dayna Danger, Camille Georgeson-Usher, and assinajaq, and was curated by Hebert-Spence. I was particularly excited to see Danger’s piece Breathe Out, which is a large print of a photograph featuring Danger wearing a beaded BDSM mask (an expression of the sexual culture(s) of bondage, discipline, sadism and masochism) that she created collectively with Nicole Redstar and Tricia Livingston. Along with the mask being a beautiful display of beadwork and creativity, Danger also wanted the piece to serve as a catalyst for conversations regarding the complexities of Indigenous sexuality and non-normative desire. Despite the history of colonization and its goal of controlling Indigenous bodies, Indigenous people have found ways to practice decolonization, forging their own paths regarding their bodies, genders and sexualities and towards a sovereign erotic future. “Sovereign erotic” is a term coined by Qwo-Li Driskill in their article “Stolen From Our Bodies: First Nations Two-Spirits/Queers and the Journey to a Sovereign Erotic” and it describes “a return to and/or continuance of the complex realities of gender and sexuality that are ever-present in both the human and more-than-human world, but erased and hidden by colonial cultures” (56)

Our final stop of the day was the University of Winnipeg to view the Anthropology Museum. Staff had placed Indigenous beadworks from North America and Africa out on tables for us to see, and provided gloves for us to handle the pieces (see figures 5 & 6). This was a neat experience since, when you think of museums, you tend to think of artifacts locked away behind glass where no one can access them. By removing the glass and inviting us to touch the beadings, a deeper connection to the pieces could be made. Additionally, the ability to look at the works from different angles, including inside the pieces, allowed participants to study the craftsperson’s techniques and materials as many participants were also craftspeople. Information such as where the item was collected, by who, and its cultural significance was provided for each piece when possible. Overall, I was impressed with my visit here. By allowing us to handle the works, I feel the Anthropology Museum recognized that these pieces are more than just art to look at—they are bridges between the past and present. This recognition was also present in their description of beadwork in connection to the collection Beads of Resistance, Resilience, and Reconciliation located in one of the display windows at the university. They describe beadwork as not only an art form but also “a spiritual journey, an act of resistance, and a path toward reconciliation”.

In A Recognition of Being: Reconstructing Native Womanhood (2000), Kim Anderson discusses acts of resistance and the reclaiming of identity. She writes, “whether at the individual level or the national level, creative expression is essential for the recovery of our identity” (144). Through Anderson’s lens, the whole beading symposium could be seen as a way to resist and reclaim—resisting the idea of “dead” or “ancient” art forms, and resisting past and ongoing colonization that seeks to sever ties to Indigenous traditions. This resistance continues through the passing on of knowledge to others, including by institutions, such as museums and galleries, as places where material culture and people gather. Reclaiming shows up as an important act of resistance as more and more Indigenous and colonized people seek out their histories. The symposium taught me that, through beading and research, we can learn about and make connections to our ancestors and past traditions. Beadwork conveys knowledge through its materials, techniques, and the stories represented within the works themselves.

Throughout Canadian history, the Indian Act has undergone many changes since its original signing into law in 1876, including various amendments that restricted Indigenous traditional and spiritual practices. Singing, drumming, sewing and ziigimineshin—which translates as “dropping beads” in Ojibway (Brandson)—are some creative forms of expression that were taken away by force in an effort to assimilate Indigenous communities into Canadian culture. Returning to Hebert-Spence’s description of the act of beading as one of love, we can see how beading can be the basis of community building, a way to defy internalized negativity and create connections that allow us to feel that we are authentic just as we are (Koncan). To seek out these practices, then, is one way to reclaim and foster our stolen identities.

Notes:

1 Unfortunately I was only able to attend the first two days of the symposium, with this blog post covering the first of the two. If interested, the symposium’s schedule can still be viewed at: https://beadingsymp.ca/Schedule (Still available as of May 1, 2020).

2 Hebert-Spence also shared another story about putting this symposium together. She talked about how a colleague and her were both planning curatorial projects and symposiums at the same time, both about beading. But instead of it becoming a competition, both celebrated it and wanted the best for one another. This solidarity was fantastic to hear about, that we can take on the same work and collectively benefit as a community.

Works Cited:

Anderson, Kim. A Recognition of Being: Reconstructing Native Womanhood. Women’s Press, 2000.

Brandson, Ashley. “Beading Symposium Brings Beaders Together in Winnipeg | CBC News.” CBCnews, CBC/Radio Canada, 9 Feb. 2020.

Driskill, Qwo-Li. “Stolen from Our Bodies: First Nations Two-Spirits/Queers and the Journey to a Sovereign Erotic.” Studies in American Indian Literatures, vol. 16, no. 2, 2004, pp. 50–64.

Koncan, Frances. “Exhibition Examines Beading’s Connection to Culture, Community and the Land.” Winnipeg Free Press, 7 Feb. 2020.

Monture, Patricia. “Race, gender, and the University: Strategies for Survival.” States of Race: Critical Race Feminism for the 21st Century, edited by Sherene Razack, Malinda Smith, and Sunera Thobani, Between the Lines Books, 2010, pp. 23-35.

Robert, Nicole. “Getting Intersectional in Museums.” Museums & Social Issues, vol. 9, no. 1, 2014, pp. 24–33.

*Chris Eastman is an Indigenous queer undergrad currently working towards a BSc in Information Technology and a BA in Theatre Productions at the University of Winnipeg. He is interested in Indigenous feminism and queer theory, as well as the role technology can play in sharing knowledge with accessibility in mind.