By Misha Falk*

In June 2018, as a Research Assistant for a team project at the University of Winnipeg called Museum Queeries, I went on a “Pride Tour” offered by the Canadian Museum for Human Rights. I was specifically interested in how gender identity and transgender communities were being represented by the museum. The only point in our tour that directly discussed transgender identity was when we stopped by the bathrooms where—to the side of the male and female stalls—we were pointed to a single stall accessible washroom which our tour guide used to highlight the importance of including people of diverse gender identities. While it is good that they have this accessible bathroom stall, it felt like the purpose of this stop in the tour was meant to acknowledge transgender people by way of raising the “bathroom issue” that is getting some attention in popular discourse [a current topic that the museum wanted to weigh in on], but not as something that was taken into account during the actual curatorial process of the Museum’s exhibits¹. I thought that reducing the expansive range of issues implicated in representing trans communities to one reference to the “bathroom issue” was a disappointing oversimplification. In thinking through questions of how trans histories are represented and the futures these histories might orient us towards, I considered how the language to describe transgender identity has changed over time, how trans people have appeared, or been left out, within broader queer spaces, and what the impacts of racism and colonialism have had both as external pressures and from within queer and trans communities. The Museum’s failure to address any of these complexities prompted me to look for other spaces of public history in Winnipeg where representations of transgender stories might be found.

Archiving trans history has some particular challenges. While certain identity categories have been used to describe the experiences of groups during specific time periods, these categories were often placed upon communities without the community’s consent, leaving them to negotiate how they related to these taxonomies in retrospect. At present, it appears that the transgender community has much greater say over how gender identity is articulated through language than they did in the past². It is important not to impose present discourses of identity onto historical understandings of language and identity. However, it is also necessary to critically examine how the language of identity is operating and how diverse experiences existed even when there were fewer categories of recognition available.

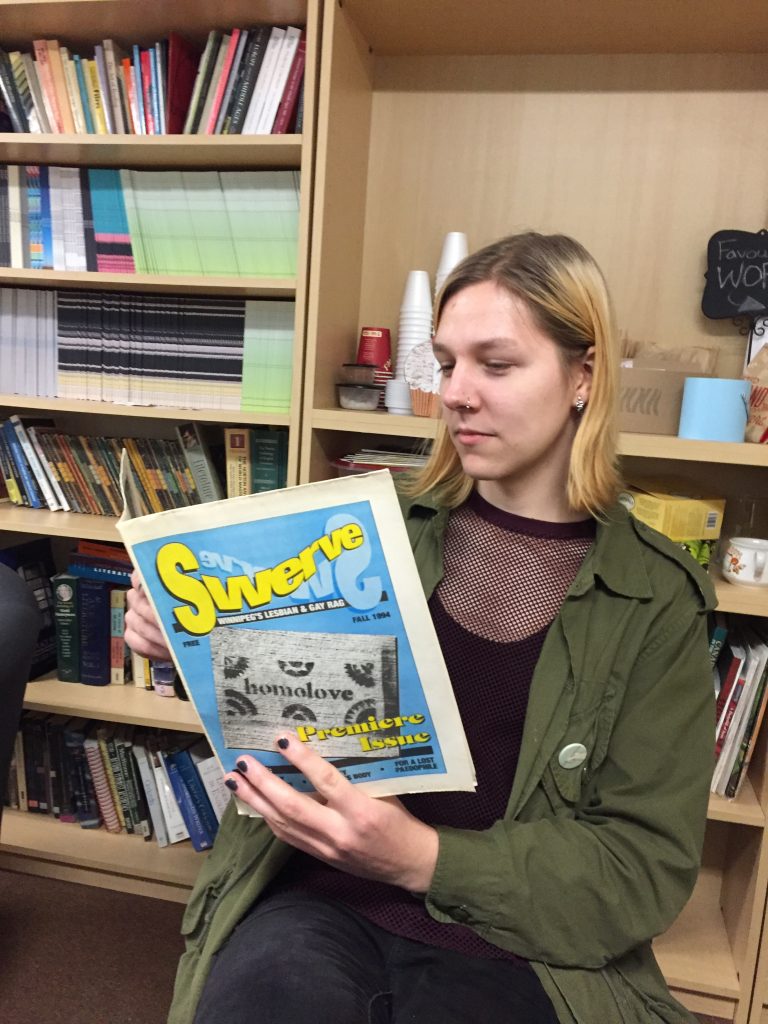

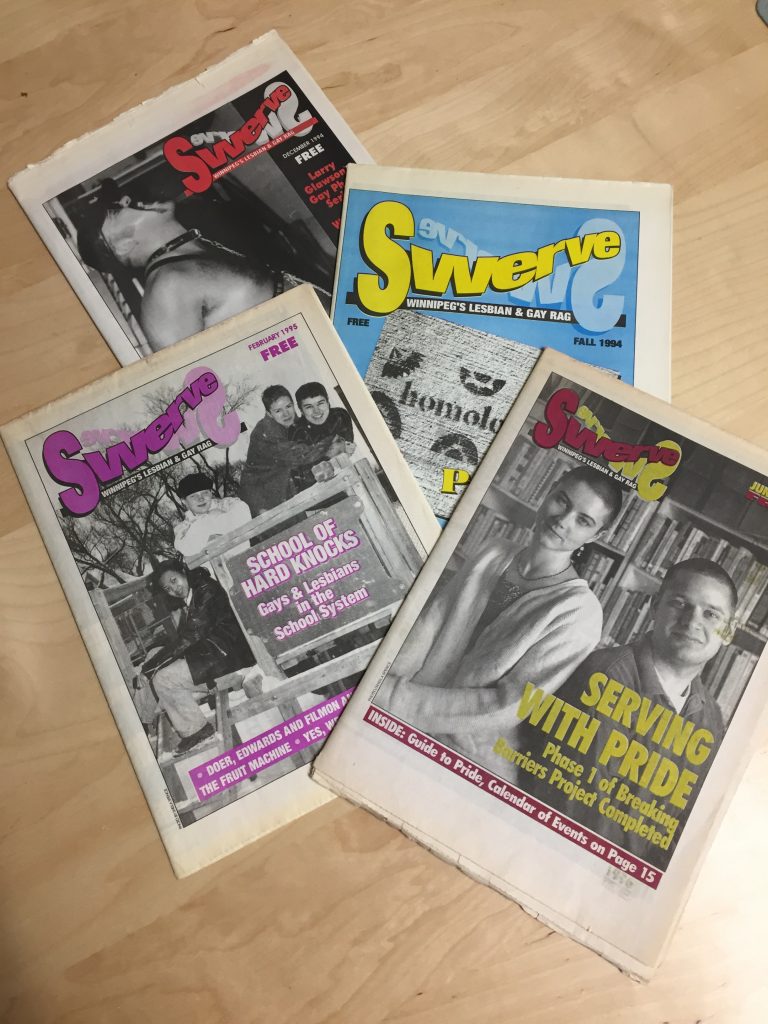

An example of the complexities of changing gender identity language can be seen in the 1994 premier issue of Winnipeg’s Gay and Lesbian magazine Swerve,which included a demographic survey of its readership. The first question asked “you are…?” with only two possible responses: ‘male’ and ‘female’. At first glance, it may seem that the publication was unaware of gender expressions that exist outside of this binary understanding; however, if you read further on, this is not the case. Later in the quiz, there are references to ‘transvestites’, ‘drag queens’, ‘effeminate men’, and ‘butch women’. The absence of direct acknowledgement of gender identities existing outside of the binary should not be taken to suggest that there was no experience or discussion of gender non-conformity. Rather, this absence can be understood through the lens of Foucault’s repressive hypothesis, as “this is not a plain and simple imposition of silence. Rather, it was a new regime of discourses. Not any less was said about it; on the contrary. But things were said in a different way; it was different people who said them, from different points of view” (27). Clearly, Swerveand its readership were aware that many people live in tension with the concept of the gender binary; at the same time, the quiz also reveals that gender was thought of differently even within queer communities at different points in history.

As new language for identity emerges, people begin to understand themselves through it and can demand institutional and cultural recognition by rallying around specific identity markers. Gender theorist Paul Preciado says “there are not two sexes, but a multiplicity of genetic, hormonal, chromosomal, genital, sexual, and sensual configurations. There is no empirical truth to male or female gender beyond an assemblage of normative cultural fictions” (265). Thinking of gender as a fiction can make it seem meaningless, but this is not the case. The normative fictions perpetuated by society are already alienating for many people, and, if gender is a fiction, then alternate fictions can be created to challenge the narrative that binary gender is an inherent truth. For instance, when ‘non-binary’ became a term in the queer community, many people who already were gender non-conforming found this term meaningful as a way to articulate their understandings of their own gender beyond the binary system that holds ‘male’ and ‘female’ to be the only essentially true expressions of gender. This is not to say that the feelings which draw people to identify with the term non-binary did not exist prior to the word emerging, but that they would have been understood differently both by the community and by larger cultural discourse; different language would have existed to articulate these experiences.

When I visited the Manitoba Gay and Lesbian Archives to do some research on transgender history, I saw this tension between how individuals and communities create language to understand themselves and how institutions negotiate this first hand. Just from its name, I could assume that the Archives would have more resources on the gay and lesbian community than on trans individuals³, but, since there is no specific transgender archive in Winnipeg, I thought it might at least be a good starting point for understanding how this community is represented within archival spaces.

In the Archives, I found the most material on transgender history in box 20, folder 6 titled “Transvestites & Transvestism, Transgenderists”. These are words very few people within the transgender community describe themselves with today. While in the study of transgender history, it is important not to impose present understandings of transgender identity on how people in the community understood themselves in the past, the fact that the majority of the contents of this folder were article clippings from the Winnipeg Sunand the Winnipeg Free Pressfrom the 80s and 90s and not content from the transgender community directly makes me think that the understandings of identity articulated within the archive do not necessarily come from the community itself.

Queers who do not fall into normative scripts, which inherently privilege whiteness and cis-normativity, are allowed into archival spaces only as recent add-ons—tokens for the institution to show how ‘progressive’ they are.

While queer archives might be assumed to be progressive or radical, the curatorial starting point of these archives are often tied up in the same projects of whiteness, colonialism and imperialism as their straight counterparts. Syrus Marcus Ware critiques BIPOC representation within queer archival spaces, observing: “this erasure is part of the larger conceptualization of the black queer subject as a new entity, whose history is built upon an already existing white LGBTTI2QQ space and history” (170). Queers who do not fall into normative scripts, which inherently privilege whiteness and cis-normativity, are allowed into archival spaces only as recent add-ons—tokens for the institution to show how ‘progressive’ they are. Ware suggests that “we start with a black trans and queer history as a way to orient us towards different pasts and futures” (170). By centering archival work being done by those who have historically been disregarded in queer archiving, the conversation around identity and representation can be opened up for many marginalized communities to have greater autonomy to represent their identities and narratives themselves rather than being fit into normative discourses.

In 2014, the University of Winnipeg held a conference called Writing Trans Genres: Emergent Literatures and Criticism.Looking at the description of the conference perhaps offers some evidence of how the transgender community—at least its literary and scholarly members— has more recently come to understand itself. The second paragraph of the conference description reads: “What is or might be Trans Literature? Transsexual, two spirit, genderqueer and transgender literatures? What are or might be trans genres, narratives, figures, poetics? What makes writing trans?” While the conference is a pretty specific context and does not represent the trans community as a whole, this flurry of questions serves as a reminder that trans cultural production and identity is not static. Instead of a folder label that tries to encompass the trans experience, questions like these reveal how trans identity is held open within certain contexts in the community as something that is actively being negotiated and resisting being fitted into boxes.

In thinking through these examples of trans representation within institutions that facilitate the creation of public memory in Winnipeg, I was struck by the necessity of critiquing sources both inside and outside the community. Trans communities are not homogenous and a multitude of experiences and expressions exist within them. As language to describe trans identity changes—sometimes at different times and in different ways across parts of the community—it is necessary to rethink how we approach archiving these histories. Centering trans communities in the archiving process, particularly QTBIPOC communities, can point trans histories in radically new directions. Questioning what has been deemed worthy of archiving, and noticing what has been left out, can open up new possibilities for imagining what trans futurity might look like.

Notes:

- While the accessible washroom was the one stop related to transgender issues on this particular Pride Tour, according to some of my colleagues other Pride Tours at the CMHR have highlighted a story on transgender musician and activist Michelle Josef which is located in the one of the digital memory banks which visitors can explore. This being said, the memory banks are extensive and can be difficult to navigate, meaning that stories such as Michelle Josef’s are hard to find unless they are specifically pointed out.

- Online platforms such as Tumblr and Twitter are examples of digital spaces where communities of primarily young trans people have played with language, debating which words to reclaim, and even inventing new terms to describe and make sense of their experiences.

- The Manitoba Gay and Lesbian Archives website includes a short sentence and hyperlink directing researchers to the University of Victoria’s Transgender Archives if they are specifically interested in this topic.

Works Cited:

Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality Volume 1: An Introduction. Random House, 1978.

Preciado, Paul. Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs, and Bioplolitics in the Pharmacopornographic Era. The Feminist Press, 2013.

Ware, Syrus Marcus. “All Power to All People? Black LBGTTI2QQ Activism, Remembrance, and Archiving in Toronto.” TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly, vol. 4, no. 2, 2017, pp. 170-180. DOI: 10.1215/23289252-3814961.

Writing Trans Genres: Emergent Literatures and Criticism. Institute for Women’s and Gender Studies, 2014, http://www.writingtransgenres.com/. Accessed 29 August 2018.

*Misha Falk is an undergraduate student working towards an honours degree in English at the University of Winnipeg. She is particularly interested in queer theory with a focus on trans subjectivities, cultural production & history.