For the past twelve weeks I have been working as a Mitacs-Globalink Research Intern with the Museum Queeries project based at the University of Winnipeg. Museum Queeries describes itself as “prioritiz[ing] Two-Spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, transsexual, and queer, (2S+LGBTTQ) contributions and interventions into museums and museum studies both as a means of addressing structural exclusions and opening new modes of productive inquiry and activism.” I was very intrigued by this research focus as I had not yet realized that there were research projects focused on queer people, which was impossible for me to imagine in China. The project requires visits to museums and our trip to the Canadian Museum for Human Rights (CMHR) has been on my mind for months. The museum’s purpose is “to explore the subject of human rights with a special but not exclusive reference to Canada, to enhance the public’s understanding of human rights, to promote respect for others and to encourage reflection and dialogue” (CMHR). I was impressed by the CMHR because it was the first museum that I was aware of that was promoting human rights. I got the chance to visit this national museum twice with Museum Queeries. The first time I went on a “Pride Tour” with my supervisors and other research assistants from July 22-23, 2019, and after that I took a self-guided tour.

Photo credit: Hubery Huang)

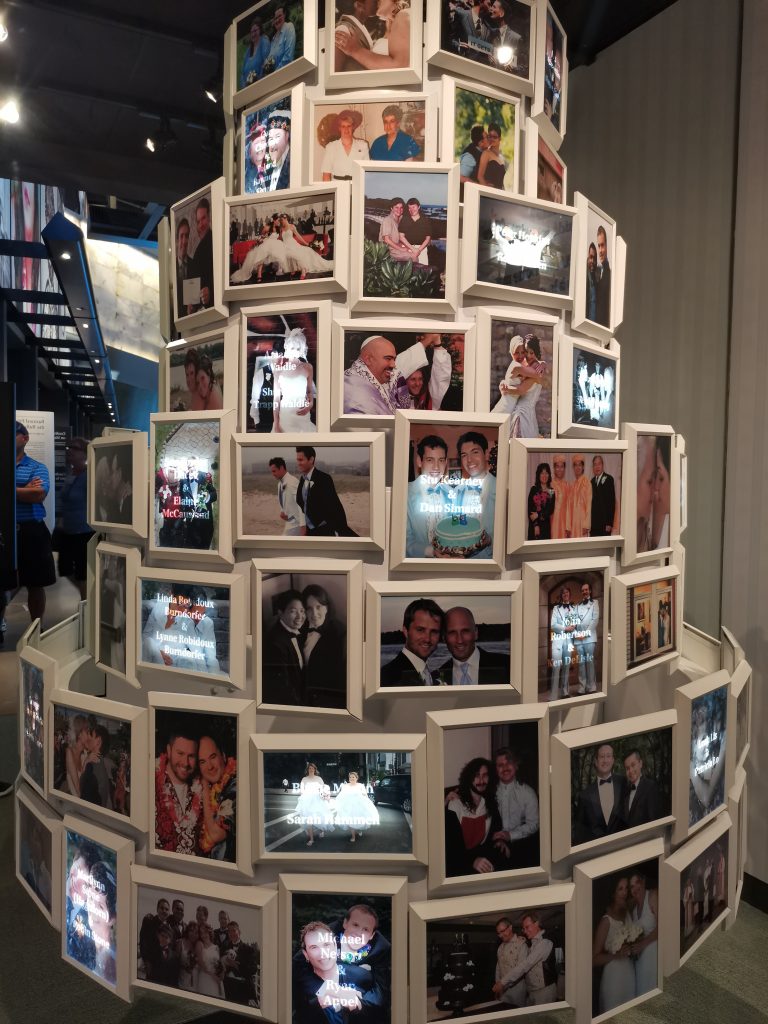

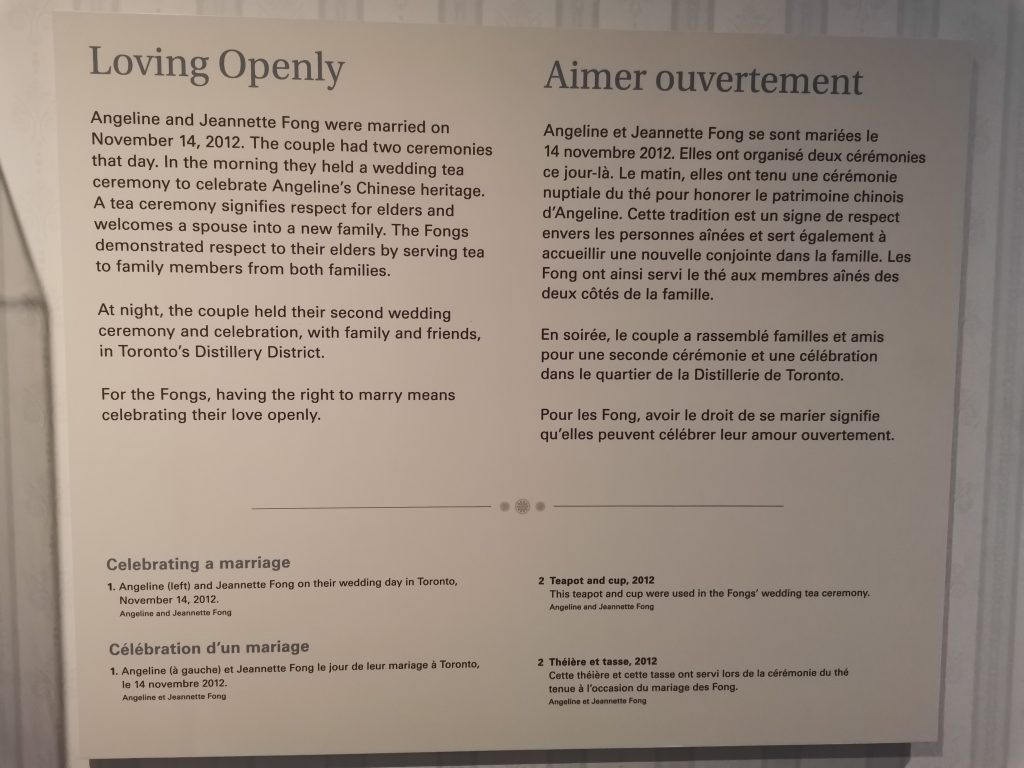

At first glance, I was particularly interested in an exhibit called “Taking the Cake: The Right to Same-Sex Marriage.” However, upon further investigation, I found myself embarrassed by the way the museum illustrated Chinese queer people. “Taking the Cake” is an exhibit in the Canadian Journeys gallery about same-sex marriage in Canada. The exhibition is a multi-layered cake—which is framed layer by layer with same-sex couples’ wedding pictures along with their names. Notably, the couples are mostly white people, while Asian faces are rare, especially those of East Asian people. At the left and right side of the cake are two couples’ stories about same-sex marriage. The left side is called “Trailblazing for the Right to Marry,” which features the story of Manitobans Chris Vogel and Richard North who were the first couple in Canada to undertake a court battle to achieve legal same-sex marriage. On the right side is a portrayal of Angeline and Jeannette Fong’s marriage in 2012, after same-sex marriage had already become legal in Canada. Angeline’s is one of the rare examples of an Asian face in the exhibit. The museum’s story emphasizes that this couple had two ceremonies, one of which was a traditional Chinese wedding tea ceremony. The panel states that “a tea ceremony signifies respect for elders and welcomes a spouse into a new family” and that “the Fongs demonstrated respect to their elders by serving tea to family members from both families” (“Taking the Cake”). This particular framing raised many questions for me.

Photo credit: Hubery Huang)

For instance, I wondered whether Angeline Fong immigrated to Canada prior to her marriage or was married prior to becoming a Canadian resident, or whether she is Canadian born. This is notable because Chinese mainland citizens do not have access to legal same-sex marriage currently. Also, as far as I know from my knowledge of traditional Chinese marriage, parents from both sides should attend the wedding and drink the tea to show their acceptance to the new family member. Once they have finished the tea, the new spouse traditionally begins to call them “father” and “mother”. In this case, why does the museum use “elders” and “family members” instead of “parents”? Does this indicate that their parents were not present at their wedding? Chinese attach great importance to filial piety, which is also one of the main reasons for the wedding tea ceremony. However, based on my lived observation, parents are usually the last ones to accept a queer daughter/son. This conflict exists in many parts of China. What was Angeline’s parents’ opinion? Have they changed their minds or supported her from the very beginning? Angeline Fong’s marriage is obviously not a typical example of Chinese queer people who would be envious of her, because most queer Chinese cannot get married or receive congratulations from their family.

Interestingly, I got to know the connotative meaning of “taking the cake”, which is “to be the winner.” When I participated in the Museum Queeries workshop after the visit, this drove me to an even more abashed situation, for the rest of the researchers and research assistants were shocked about my talking about Chinese queer people’s real lives. Many queer people around the world like Chinese have not been “winners,” yet the museum includes a Chinese style wedding ceremony without recognizing this difficulty. Also, while the panel discusses Angeline Fong’s cultural heritage, her nationality or citizenship status is unclear. For me, not knowing if she is Chinese or Canadian born makes a difference. By portraying Angeline Fong’s marriage as fully accepted, the museum easily misleads Western/North American visitors to think that Chinese same-sex marriage is as easy as it is for Canadian queers, which is absolutely wrong.

Photo credit: Hubery Huang)

The way the museum tells the Fongs’ story might make visitors think that Chinese parents are all open about same-sex marriage, or that parents are not obstacles to getting married. One reasonable explanation could be the fact that the curators are working from a western perspective, and their culture does not highlight filial piety as Chinese people do. Their preconceived ideas concerning the relationship between parents and offspring have been limiting their understanding of queer life in China. The museum also gives visitors a fake impression with respect to the Chinese queer community: as long as same-sex marriage becomes legal in mainland China or they get married in Canada, there would be no other problems for same-sex couples such as family objection.

However, the real circumstances are more complex and knotty. According to the largest national survey ever conducted on sexual and gender diversity issues in China by the United Nations Development Programme – BEING LGBTI IN CHINA, A National Survey on Social Attitudes towards Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Gender Expression, “Sexual and gender minority people in China still live in the shadows, with only 5% of them willing to live their diversity openly.” Most LGBTI people are facing discrimination in many aspects of their lives, and the family is the place where the deepest forms of rejection and abuse reside, and discriminations occur most frequently. While most get into heterosexual relationships under family pressures, some decide to have “cooperation marriages.” Statistics show that more than half of the families reject the minorities; nearly two thirds of minority respondents suggest that they feel under great pressure from their families to get married and have children. Among the married minority respondents, nearly 84.1% are married with heterosexuals, 13.2% are in “marriages of convenience” and 2.6% in same-sex marriages are registered in foreign countries. These findings strongly prove the fact that family is the biggest barrier to queer community in China.

The filial piety spirit in traditional Chinese culture can account for the complexity of the potential for same-sex marriage in China. There is a Chinese saying: “Among hundreds of behaviors, filial piety is the most important one.” Meanwhile, the relationship between parents and children are much more closed than westerners. For Chinese parents, children are the centre of their lives, and they are willing to devote everything to their kids including high-expense education, residence, wedding and caring for their grandchildren. Moreover, the deep-rooted idea of getting married and having children also exist nowadays as an essential way of showing filial piety. Even a heterosexual person that refuses to get married or does not give birth to a child would be likely to be considered as the black sheep of the family. Due to the deeply rooted bias which has existed for thousands of years about marriage, Chinese queers are experiencing more difficulties than westerners.

Living in a cultural background like this, Chinese queers have different opinions about their right to marriage. As the above statistics show, most queer people have to marry heterosexuals as they get older. Some young people have more freedom to refuse to get married or to marry abroad, but this is uncommon. When talking about “coming out” to parents and marriage, many choose to hide their sexual orientations and put off their marriage on the pretext of having a busy job. Some bolder couples would take their partner to family under the name of “good friends”.

Nevertheless, an important recent event that encouraged discussion of same-sex marriage in China was Taiwan’s legalization of same-sex marriage on 24 May 2019, making it the first region in Asia to legalize same-sex marriage. Though the official media mostly ignored it, citizens from across China enthusiastically posted blogs on Sina Weibo and Wechat with tags like “love is love” to celebrate the success. It soon became a top trending topic and achieved more than 200 million readers and participants on Weibo.

In mainland China, proponents of same-sex marriage also exist. One example is Sun Wenlin. Sun Wenlin and Hu Mingliang are gay Chinese partners who applied to get married in 2015. After being refused by Changsha city authorities, they filed what is in fact the first lawsuit about same-sex marriage in China. In an interview, Sun says that “the original text of the Marriage Law does not say one man and one woman, but a husband and a wife” and that they personally “believe that this term refers not only to heterosexual couples but also to same-sex couples” (Jie). However, the case wrapped up quickly and they unfortunately, yet unsurprisingly, lost. Despite the failure, Sun and Hu still planned to hold their wedding on May 17, 2016, the International Day Against Homophobia. Their wedding attracted more than 10 media outlets and their stories were reported both at home and abroad.

After the case and wedding, Sun continued to promote same-sex marriage. He is working on a project for “100 Same-Sex Weddings,” and to date eight weddings have been held successfully. Half of the couples’ marriages were admitted by family members from at least one side of the couples, and some also gained support from their families after weddings. Sun notes that “one wedding can be small, two weddings may also be ignored, but if we can have 100 couples wanting to get legal union, people cannot neglect us” (Jie). Luckily, the weddings have attracted some international media and public attention.

Apart from wedding ceremonies, Sun also wants to amend the law. In 2018, Sun posted an article on his social media to encourage and instruct people to make suggestions for the civil code in order to legalize same-sex marriage. The reason for Sun’s persistence is that he wants to have legal documents to protect them from catastrophes like being separated by others or being unable to be each other’s next of kin. As the gay law student Jack Baker said, “Whatever rights straight people have, I want too.” He argued that “the institution of marriage has been used by the legal system as a distribution mechanism for many rights and privileges, [which] can be obtained only through a legal marriage,” and to legalize same-sex marriage would give queer people “a new dignity and self-respect” (Chauncey).

In fact, although Sun has done so many things on the website, not much change has manifested yet. His lawsuit did not get much attention from the public. The more disappointing fact is that even LGBTQ people like me also know little about his work. It is still sensitive in China to talk about queer identities. We can imagine that most Chinese people, like the government, tend to avoid gay things on the internet, and the people who advocate same-sex marriage and queer rights are either brave queer people or open minded heterosexuals, and they are few. For the middle-aged and elderly people who seldom surf the internet, queer topics can be a huge taboo. Therefore, due to the conservative environment, most queer people choose to hide and get married with heterosexuals. Meanwhile, as it is not common in China to parade or fight against the authority, the call for same-sex marriage is not loud at all.

Intriguingly, as the younger generation becomes more and more progressive and have more access to know the world, their thinking about marriage has changed. Just like many westerners, they do not think marriage is necessary and they are more concerned with their career as well as the relationship with their partners. This might challenge the presumed requirement of marriage and present co-habitation as a preferred option for both homosexuals and heterosexuals.

When I take a look at Canadian lesbian and gay liberation, it is noted that “most queer liberationists dreamed of the day that marriage would be abolished altogether” (Knegt). Just like the liberation activist Gerald Hannon said, “We took a constructionist view of homosexuality, and thought that all people should be free of repressive social institutions like marriage that bring with it traditional gender and sex roles. The government should be out of the marriage business period. We shouldn’t be trying to get in” (Knegt). Brenda Cossman also argued that governments should pursue a “more comprehensive and principled approach” to the legal recognition and support of the “full range of close personal relationships among adults” (Knegt). But there is one important point: though many queer Canadians do not get married, they do have legal common-law rights with their partners and children. According to Statistics Canada’s census of population (2006) there were 45,345 co-habitating same-sex couples in Canada, which is more than 6 times that of the same-sex marriage statistics. In this way, perhaps there is a common trend among Chinese and Canadian queers to define their relationships outside of legal marriage.

By comparing the different cultural backgrounds between Canada and China, we can assume that Chinese queer people will have a long way to go before same-sex marriage is legalized, and that it is not as simple as suggested by the CMHR’s “Taking the Cake” exhibit. It would be more effective for the museum to use several sentences about the reality of queer lives in China so that misconceptions could be avoided and western visitors could appreciate the complexities. As a queer Chinese, I cherish this research so much as it takes me on a new journey and makes me think ahead: what is the way for the Chinese queer, and in what ways can we achieve the human rights that Canadian queers seem to have? I believe there is a lot that we can borrow from this history, and the future for us could be promising that someday, we can really “take the cake.”

Thank-you to the Fongs, Angeline in particular, for sharing their story and appearing in the “Taking the Cake” exhibit so that I could have the opportunity to explore this topic.

Works cited:

CMHR. “Our Mandate.” Canadian Museum for Human Rights.

Jie, Jiang. Court accepts China’s first gay marriage rights lawsuit. Globaltimes, 6 Jan. 2016.

Chauncey, George. Why Marriage: The History Shaping Today’s Debate Over Gay Equality. Basic Books, 2004.

Knegt, Peter. About Canada Queer Rights. Fernwood Publishing, 2011.

Le Bourdais, Céline, et al. “Changes in Conjugal Life in Canada: Is Cohabitation Progressively Replacing Marriage?” Canadian Perspectives in Sexualities Studies: Identities, Experiences, and the Contexts of Change, edited by Diane Naugler, Oxford University Press Canada, 2012, pp. 223-234.

“Taking the Cake.” Exhibit in the Canadian Journeys Gallery, Canadian Museum for Human Rights.

United Nations Development Programme. “BEING LGBTI IN CHINA, A National Survey on Social Attitudes towards Sexual Orientation, Gender Identify and Gender Expression.” 16 Jan. 2018.

*Hubery Huang is currently studying at Northwest A&F University as an English major in China. She is particularly interested in queer theory and how LGBTQ groups influence museum cultures. She joined the Museum Queeries project as a Mitacs Intern for 2019, and was sponsored in part by the China Scholarship Council (CSC).